Yvon Chouinard is no regular company founder. He started a company simply because he was a dissatisfied consumer of rock climbing equipment, who wanted to make climbing gear that was built to last.

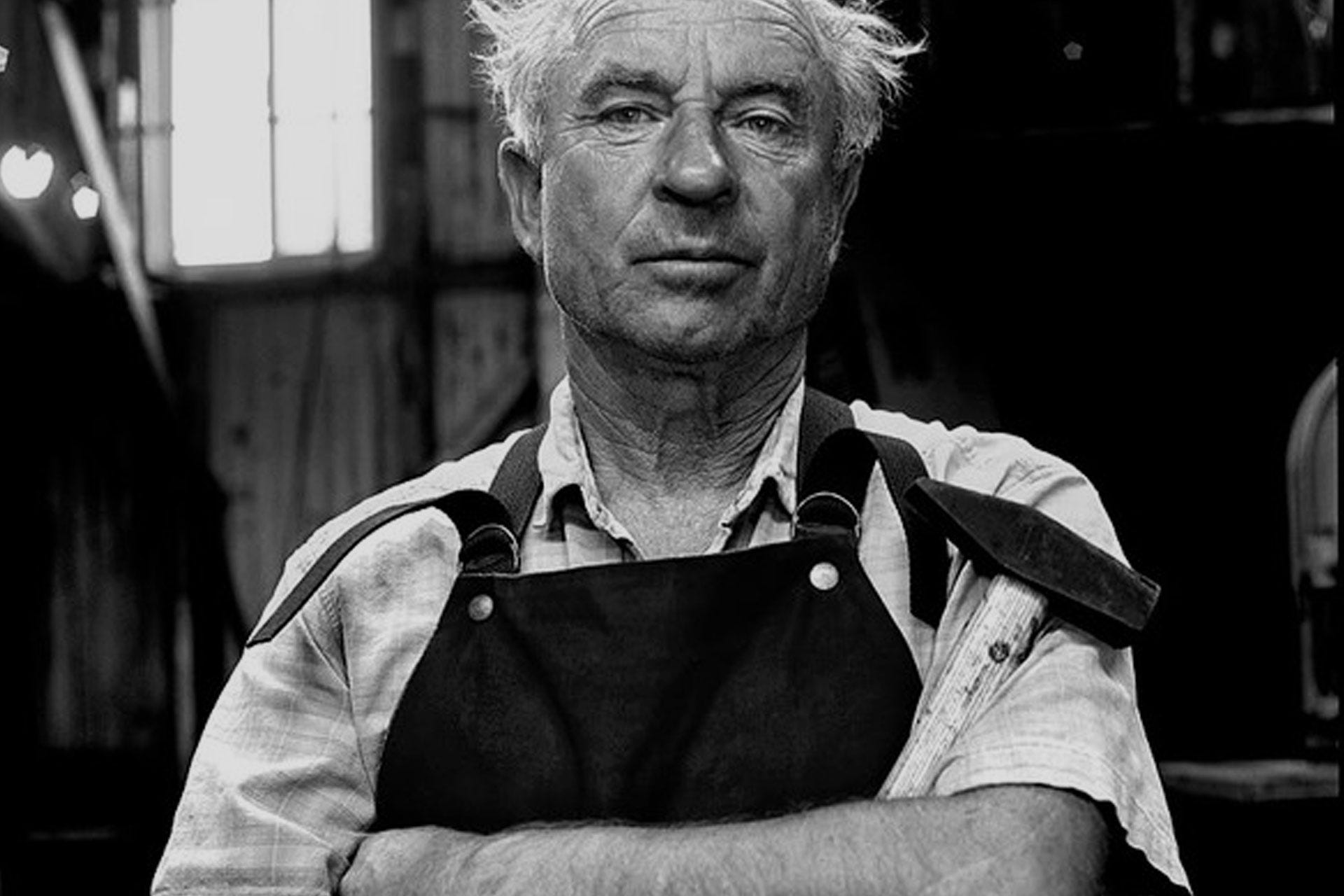

Yvon Chouinard founded Patagonia in 1973, and calls himself a “reluctant businessman”

With a unique combination of anti-consumerist beliefs and an appreciation for high-quality products, he started Patagonia to solve his own pain points as a climber, and not to make money.

After 43 years, he still owns 100% of the private company, refers to the company as “family”, and harbours a slight guilt over being part of the consumer world. Even those who disagree with his beliefs would likely hail him as a remarkable person.

What I am most interested in is how Chouinard built and preserved such a distinct brand, and how we might use some of his practices in our own work as marketers.

1. Create Something You Would Want Yourself- Chouinard only launched new products or services, or made changes to products, if he deeply felt there was a need to make it better. Most of what he launched in the early days were through observations of what could be made better in existing products in the market, and he cites his greatest gift as the ability to identify what can be improved. My favourite story about Chouinard is that he started making rock climbing apparel only because he loved wearing tougher-quality, colourful rugby shirts while climbing. He was a consumer first, marketer second- and that made a big difference in satisfying his market.

How to put this into practice if you’re a marketer: immerse yourself in the online content of your core consumer. If you employ a research agency, then tag along to qualitative focus groups even if you work on the brand marketing team and have no reason to be there.

Yvon Chouinard takes several months off work every year to go fishing, citing his trust in his team as the reason he is able to do so

2. Be Really, Really Choiceful: Every brand claims to be choiceful in the decisions it makes, which is why I added “really, really”… no BS should be allowed when assessing this. For Chouinard, opening up tailoring stores that would service Patagonia clothing for a lifetime was a decision made to preserve the brand’s sustainability manifesto, despite the fact that this meant less new sales of the clothing. As Guy Raz puts it in the NPR podcast in which he interviewed Chouinard, “Yvon Chouinard basically was telling consumers, ‘don’t buy our product’”.

How to put this into practice if you’re a marketer: When choosing the “single most important thing” a campaign should stand for in your brief, or when evaluating priorities for your brand for the next year, ask yourself- will this decision result in any kind of compromise or loss (for instance, loss in disengaged consumers and consequent revenue)? If your decision has no adverse consequence whatsoever, you’re probably not being choiceful and are trying to please everyone.

3. Pretend Like Your Brand Will Be Around for the next 100 years: Chouinard doesn’t see the need for the brand to show consistent growth of X% year-on-year. He recognizes that if the company follows what is right for its consumers, some years it will show a marginal growth number, and other years might reap the benefits of good medium and long-term decision making and grow as much as 50%. This is in stark contrast to the business goals of publicly traded giants. This allows Patagonia to lend a careful ear to the lovers of its brand, and build something that will last to serve them, even if it doesn’t reap benefit in the short-term.

How to put this into practice if you’re a marketer: When working on something that will have a spike in short-term sales, also consider how you will lap that positive growth and whether it is something that will meet a need for a longer period of time. If not, perhaps the short-term campaign can be built to fall under an umbrella campaign with more clout in the long-term.

To read the original published article, click here.